Ventura County Star

When Deresa Teller arrived at ground zero on the night of Sept. 12, 2001, smoke was rising from the wreckage of the World Trade Center, and bits of paper and dust were still floating around.

A paramedic and veteran search dog handler, the Simi Valley resident had experience with large disasters. She had responded to the 1994 Northridge earthquake and the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, but was still amazed by the scope of the devastation in New York. Looking out over what rescue workers called “the pile,” she saw no furniture, clothes or computers, just a vast expanse of metal girders and dust.

“You couldn’t see an end point,” Teller said. “No matter where you looked, there was damage.”

Part of the first wave of emergency responders from California who went to New York City after the 9/11 attacks, Teller was among a small number of Ventura County residents who participated in rescue and recovery efforts directly at ground zero.

Teller was a local dog handler with connections to the Ojai-based National Disaster Search Dog Foundation. Others included four Ventura County sheriff’s deputies with New York ties and several local Red Cross volunteers.

Teller was sleeping at the Winnetka fire station, where she worked for the Los Angeles Fire Department, when she awoke Sept. 11 to an announcement that all nonemergency activities would be canceled because of the events in New York. Soon she was glued to the television, watching in horror as the World Trade Center towers came down.

She and Bella, her border collie trained in disaster search and cadaver recovery, were part of the Los Angeles City Federal Emergency Management Agency task force. They headed to the East Coast and made their first trip to ground zero the next evening.

Teller initially thought it looked like something out of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s “Terminator” movies.

“My first impression was they are not going to find anyone alive … or if they do, how the heck are they going to get to anybody with all this rubble on top of them?” she said.

She wondered, “If a chair can’t survive, how’s a human going to survive that?”

As they traversed the massive pile of rubble, searchers and dogs had to walk along metal girders, treading carefully to avoid falls that could be 30 or 40 feet, Teller recalled.

Now an inspector with the fire department, Teller said she was amazed at how well the team did in the challenging circumstances, and that there were no major injuries to the rescue workers in her group.

While they didn’t find any survivors, Teller and Bella helped recover the remains of about two dozen victims, she said.

The border collie found one victim buried about 4 inches under the surface and another deep in the rubble inside a van. In one area, Bella alerted rescuers to the remains of about 20 people, including a number of firefighters, Teller said.

Battling emotions

Remembering the emotional strain of the response to the Oklahoma City bombings, Teller made a conscious effort to avoid looking at the wall of photos of the missing. She needed to focus on the task at hand without making it personal, she said.

Meanwhile, several fellow search dog teams from Ventura County were stuck at a training session in Tacoma, Wash., when air traffic was grounded after the terrorist attacks.

Howard Orr of Newbury Park, now a Santa Barbara County Fire Department captain; Ron Weckbacher of Thousand Oaks, a civilian volunteer; and Debra Tosch of Ventura, now the search dog foundation’s executive director, had to finish the training, rent vans and drive back to California.

When they finally arrived at a military base in New Jersey 11 days after the attacks, the first thing Tosch noticed was a pervasive sense of tension, she said. Everyone on the base was carrying guns, and handlers were told that anyone who left a designated area would be shot, she said.

Orr remembers being driven to ground zero on a tour bus, past streets lined with people holding flags and banners as they cheered volunteers. There also were people holding — and walls covered with — pictures of the missing, he said.

“It would put everything into very quick perspective,” he said.

Tosch remembers feeling overwhelmed by the devastation when she first saw it. “My first thought was, where do you even begin to search this?”

Her black Lab, Abby, however, was pulling at her leash. Although no survivors had been found since the effort’s early days, searchers continued to look.

“It was our job to treat every day like it was day one,” Tosch said. “Our main job is to make sure no one is left behind.”

Orr said 6,000 people were initially thought to be missing, and when he looked out over the rubble, his first thought was, “Where are they?” Authorities later determined more than 2,700 people died in New York.

Like Teller, Orr was surprised he didn’t see any desks, computers or huge pieces of concrete.

“You didn’t see any of that. It was just bent, twisted steel,” Orr recalled. “The biggest piece of concrete I saw was the size of my fist.”

Occasionally, he was surprised to find small items like a newspaper or a chafing dish intact among the rubble. Another time, he found a pristine office — complete with a family photo and a half-full cup of coffee — amid the destruction, he said.

When their dogs weren’t searching, Orr remembers working in human chains as they cleared layers from the pile.

Tosch recalled squeezing past mangled steel into voids in the rubble to look with special cameras for survivors, she said.

Many times, searchers didn’t find bodies, just pieces. But Tosch said the grief of survivors was harder to view than gruesome remains.

She recalled scenes of firefighters paying homage to fallen comrades when their remains were found in the rubble. Whenever a police officer or firefighter was found dead, everyone would stop working, take off their helmets and bow their heads while the flag-draped body was taken away.

“To see the emotions of the firefighters, the tears running down their faces — that’s what breaks your heart,” Tosch said.

She vividly remembers when searchers found a piece of equipment with a firefighter’s name on it. She and her dog searched for the firefighter as a crew from a nearby fire station looked on. When she told the chief the search had come up empty, he looked at her with sadness and said, “We didn’t expect to find anything, but you were our last chance.”

“You felt like you were disappointing so many people. You really wanted to find that firefighter for them,” Tosch recalled.

Answering the call

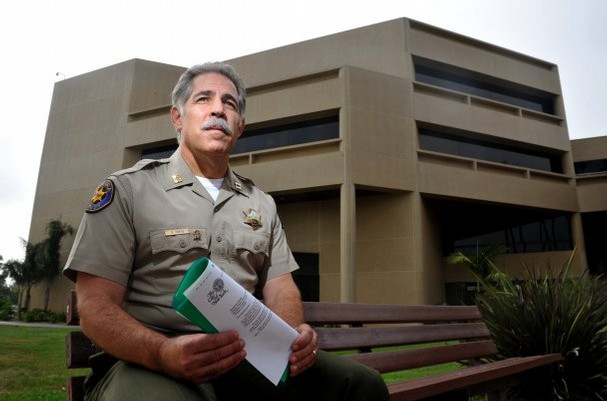

In early October, Randy Pentis, Peter Frank, Luis Alvarez and Roland Ogawa took vacation time from the Ventura County Sheriff’s Department and headed to Manhattan at their own expense. The New York Police Department had put out a national call for assistance, and the deputies wanted to help.

When Frank first saw ground zero, he felt a sense of awe that the towers were gone, he said. Raised on Long Island, he had often visited the World Trade Center with his father as a child.

“I remember you couldn’t see the top of the building when you stood on the sidewalk looking up,” said Frank, a senior deputy sheriff.

The deputies worked with New York police to guard donated goods at a warehouse facility and check the identification of people trying to enter a pier area, said Pentis, a sheriff’s captain. The work was routine, but the experience was not, he said.

“It’s one of those things that meant a lot to me,” Pentis said. Ten years later, he still keeps a letter of thanks from NYPD in his desk, he said.

“It was an event that changed the world,” Pentis said. “We wanted to help in some way.”

Orr went on an informal public relations tour when he returned, giving a firsthand account of ground zero to various groups. He wanted to convey the reality of the disaster, he said.

“Nobody was really seeing what it was like to go inside the pile of ground zero,” he said.

The experience also drove home the importance of training for disaster response, said Tosch.

“I have to know I did everything I could to prepare and we were ready when that call came and we made sure that in the areas we covered, no one was left behind,” she said. “That enables me to sleep at night.”